Wednesday Investigations [2:8]: Diabolical houses and invisible archives

On a record label in Finland, an isolated island in the Baltic Sea, and an apartment building in Poland

In July of 2004 I was on a car ride with Loren Chasse, a musician and educator known for his work with field recordings and with the sonic properties of objects which would traditionally be considered “nonmusical.” Loren was also one of the members of the then-active psychedelic improvisatory collective known as Jewelled Antler, which some of you may remember as operating on the edges of the “freak folk” scene or what WIRE journalist David Keenan referred to then as the “New Weird America.” Jewelled Antler is no more, to the best of my knowledge, although many of the participants still make music, including Loren himself: the last release of his I picked up was one made he made at home during COVID quarantine (instrumentation: “autoharps, metalophone, synthesizer, field recordings, objects”) and most recent one looks like this one from November 2022 (instrumentation: “glass panel, wire/nylon brushes, 1930s era Decca victrola, sandpaper, shells, autoharp, electromagnetic fields, dried lichen, foghorn, paper, resonators, mouth organs, field recordings (Costa Rica, Crete, and Croatia) and melodion.”)

Anyway, on that car ride Loren introduced me to some of the bands on Fonal Records, a Finnish label. As it turns out, Finland was having its own freak folk moment around that time (some, following Keenan’s lead, have referred to this parallel scene as the “New Weird Finland.”) The WIRE covered this scene in December of that year, and Pitchfork covered it in April of 2005. As for me, I made a note of it on the car ride, put it in the notecard index, and spent the next few years digging into that scene. I was fortunate enough to see a whole bunch of these Finnish artists—Lau Nau, Kuupuu, Islaja, and Tomutonttu (aka Jan Anderzén, ringleader of the Kemialliset Ystävät collective)—in the fall of 2005, when they performed in Chicago, and I even provided crash space for some of them, though I can’t exactly remember which ones.

If you’re a fan of weird music, the Fonal catalog remains a great place to begin exploring. Pitchfork describes a single Fonal release, Kemialliset Ystävät’s magnificent Alkuhärkä, as “elegantly discombobulated […] You'll hear sunny Thinking Fellers in spots, a weirdo Bach partita, backwards Ghost drone, expert toy piano, Angus MacLise hand drums/flutes in others. Also, there's a mystical butterfly theme and gongs and chimes.” (My own attempt to nail an overall label aesthetic, in a blog entry I wrote in 2011, was to call it an “uncategorizable […] blend of noise, tribal rock, children's percussion, sing-along song, and whatever else they can jam into the mix.”)

The label’s pace of release has never been forbiddingly brisk (they’ve been around for nearly 30 years but have only around 100 releases) and they remain active. It isn’t all unhinged psychedelia anymore (their most recent release is this charming bit of cheerful Finnish pop, and some of the weirdest artists from their roster have gone elsewhere), but the label page at Bandcamp is still worth checking in on a few times a year. And it can inspire some odd wanderings. Prove it, you say? Well…

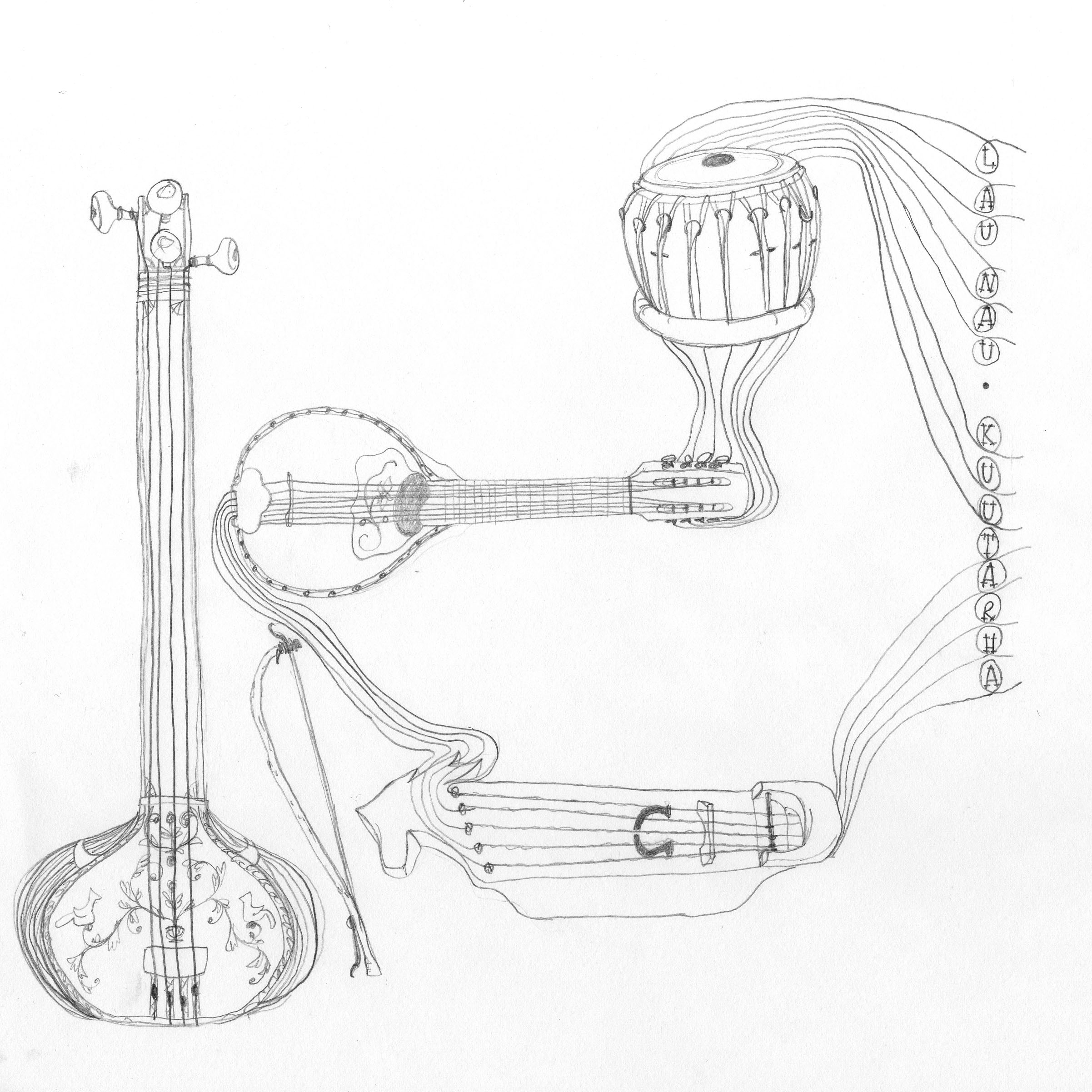

In 2020, I spotted a new Fonal release by Lau Nau, aka Laura Naukkarinen. I’d enjoyed Naukkarinen’s debut album, Kuutarha, a set of ten folk songs sung in Finnish. Initially a self-released CD-R with handmade packaging that included twigs and branches (I was able to get the more widely available reissue, released in 2005 on Chicago’s Locust Records), Kuutarha has a sparse, starkly produced sound, despite the surprisingly long list of deployed instruments: jouhikko (a fiddle played on the knee, performed by Pekko Käppi), acoustic bass and banjo (performed by Tomas Regan), flutes, kantele, chimes, and mandolin (performed by Antti Tolvi), as well as “tamboura, five-stringed kantele, acoustic guitar, violin, colorful juice glasses, mortar, mandolin, witch laugh megaphone [!], baby’s rattle, bike bells, banjo, cowbells, electric guitar, organ, willow whistle, tablas, percussion, cymbals, comb, [and] beer cans” (all performed by Naukkarinen). The cover art feels appropriate: it’s minimalist, almost skeletal, while also giving off a sense of mysterious, flowing energy:

The 2020 release (her seventh) was a film soundtrack (she’s done a fair amount of soundtrack work, including for this film about the author and cartoonist Tove Jansson, which may interest some of you). This 2020 soundtrack, though, is for the Finnish film Själö—Island of Souls, directed by Lotta Petronella. I hadn’t heard of this film before, which interested me, so I looked it up. Here’s the description from Petronella’s website:

For centuries, a closed institution served as a final destination for socially transgressive women at Själö, an isolated island in the Baltic Sea. The outcast women were kept there in detention, to be observed, studied and measured – in much the same way as the surrounding nature is by scientists at the now converted research center.

While a young scientist is collecting samples around the island, the past emerges in the whispers of the unsent letters and empty rooms of the hospital. The space fills up with hidden memories as the invisible archives come alive. Whose stories are remembered and whose are forgotten?

Trailer:

As you might expect, the soundtrack is extremely haunted, all the more so because of the choice to mix the minimal instrumentation (modular synthesizer, piano loops) with field recordings captured on the island itself by the film’s sound designer, Janne Laine. Naukkarinen’s press release about the soundtrack describes the vibe: “We hear how the island breathes in the night time, how the morning rises after the fog disappears, how the lamps are lit in an empty field research center[.]”

At the time that I learned about this album (and film), I tweeted the following:

A Finnish documentary about an "an isolated island in the Baltic Sea" that housed an institution "for socially transgressive women" sounds like discomfiting viewing, but if SJÄLÖ - ISLAND OF SOULS ever makes it to the US market I will check it out

— Jeremy P Bushnell 🐀 | jbushnell @ cohost.org (@jbushnell) 2:30 PM ∙ Oct 18, 2020

Aaaand… that brings us to this week, when I was updating my list of films I’m interested in watching (it will probably not surprise you to learn that I am the kind of nerd who maintains such a list; the number of films on it is in the high triple digits if you must know). “I wonder,” I thought to myself as my eyes alighted on the listing for Själö—Island of Souls, “whether that ever did make it to the US market?”

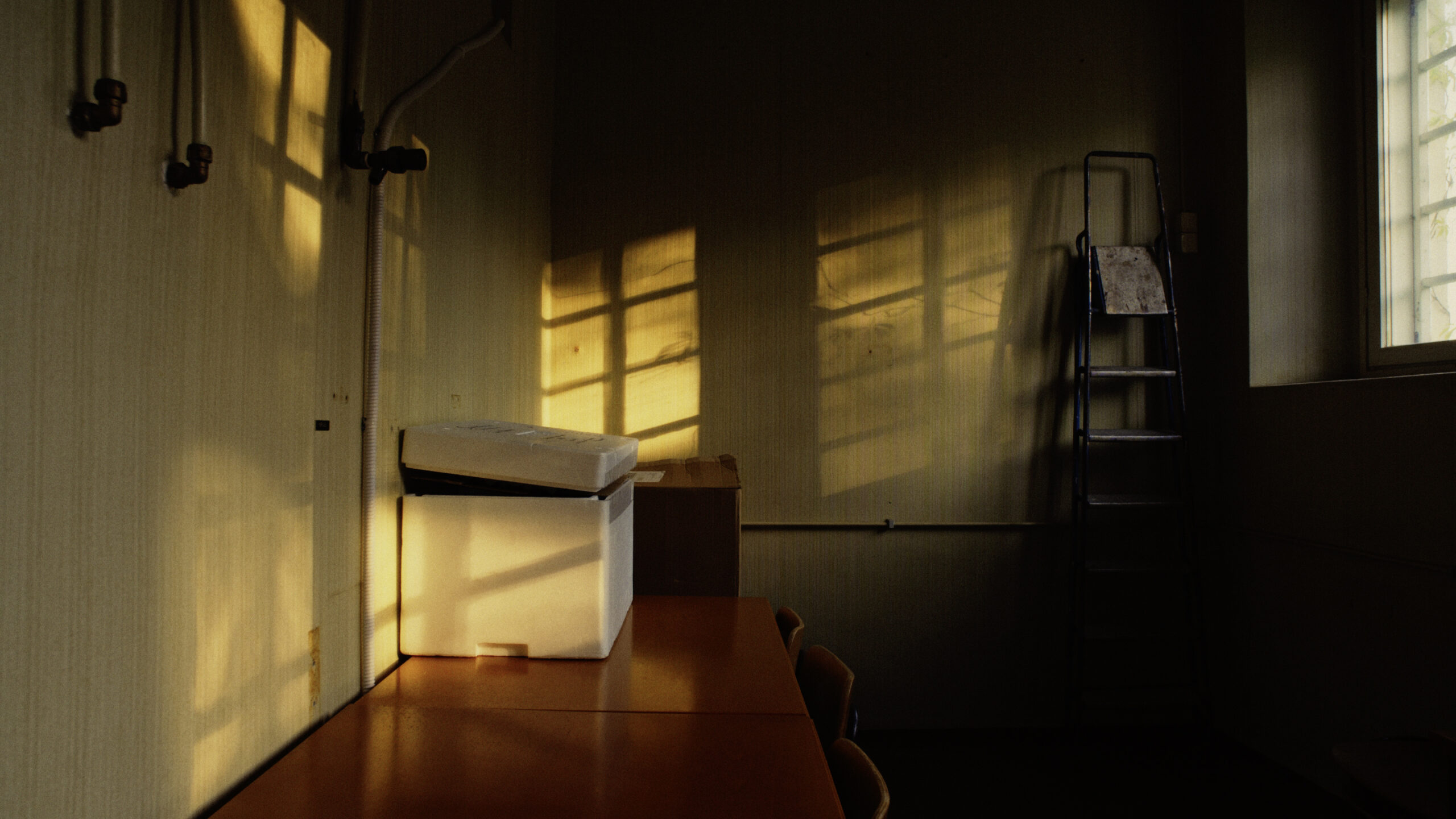

I don’t know if it ever got anything like a theatrical release over here, but a quick search did reveal that it is currently available on the streaming platform Hoopla. Hoopla makes its money by providing its service to libraries, so if you have a library card, you may very well have free access to Hoopla, and Själö—Island of Souls is well worth your time. You could pair it with Skinamarink (last seen in this newsletter back in 2.5) and have a pretty good double feature about uncanny, empty interiors:

It’s wrong, though, to treat Själö as concerned merely with “haunted vibes” or with the aesthetic veneer of eerie spaces. Yes, like Skinamarink, the film uses empty space as a way to invoke the vast suffering of vulnerable people; but even here drawing the parallel is rather glib, because, of course, unlike Skinamarink, the people this film is concerned with were real; the suffering the film concerns itself with was real. You don’t need to imagine a fictional diabolical house to disquiet yourself; you need only turn your attention to the diabolical houses that really exist. They still stand, this film says, they still stand, and it is a moral act to bear witness to them.

It bears this witness most effectively, to my mind, neither from its (haunting) visuals nor from its (absorbing) sound design but rather from its voiceover—what we hear is someone (who you don’t see) reading to us, reading letters, letters written by women trapped in this place, letters which remain in the building’s repository of papers. These letters were, you eventually realize, never mailed. Listening to them being read aloud is a harrowing experience.

The film mediates explicitly upon its reliance on this archival material, it ends with a formal mediation on archives, both official and unofficial (or, in the film’s terms, both “visible” and “invisible”). In this way it linked the film, in my mind, to a book I finished this week, Menachem Kaiser’s Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure, which begins with a young man attempting to reclaim an apartment building in Poland that had belonged to his grandfather prior to the Holocaust. This serves as a starting point for deeper a meditation upon different types of value—“historical, material, sentimental”—and plunges him into an “ouroboric spiral of questions of family, history, justice, … memory, meaning,” and more. Watching him attempt to use the few tools he has on hand—some archival records, a single notable written document, and the Polish bureaucratic apparatus—to work his way through these questions, to learn what was happening in the “heads and hearts” of his ancestors, gives the book a peculiar anguished poignance.

“[S]tories like this,” Kaiser writes, “stories that go so suddenly dark, have momentum, they invite us in, invite us to imagine…”

Whose stories are remembered, and whose are forgotten?

—JPB, writing from Dedham, MA, in the week ending Wednesday, Feb 1

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)