Wednesday Investigations [2:11]: Glenn McDonald

Discussing the information space of recorded sound with Spotify's former data alchemist

![Wednesday Investigations [2:11]: Glenn McDonald](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/04/glenn-mcdonald.jpeg)

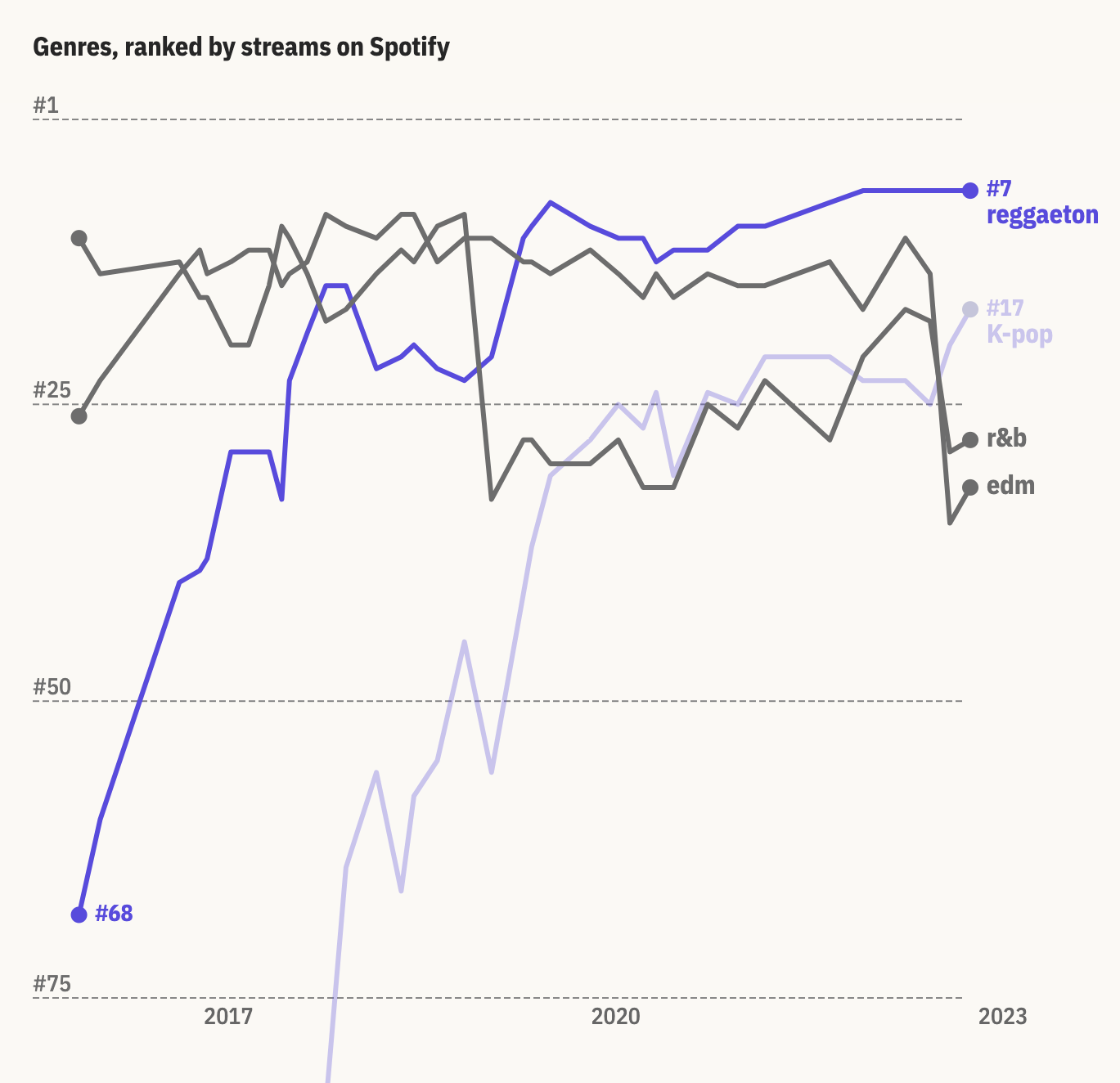

A few months ago, I came upon a visual essay at visual-essay site the Pudding about how Spotify manages genres. It begins by looking at differences in the 25 most popular genres on Spotify between 2023 and 2016 (the year Spotify first published a list of its most popular genres). The authors look at certain genres and offer some thoughtful analysis about why these genres might be rising or falling in Spotify’s metrics.

And, interestingly, they also look at how Spotify deploys genre classification in the first place. For instance, in 2022 Spotify elected to retire the catch-all Spanish-language category “Latino,” in favor of more fine-grained classifications like “Latin Pop,” “Latin Hip Hop,” and something called “Urbano Latino.” Similarly, any track in the “Hip Hop” genre might also find itself classified in hundreds of other categorical buckets—befittingly, given the ongoing stylistic flowering of the genre.

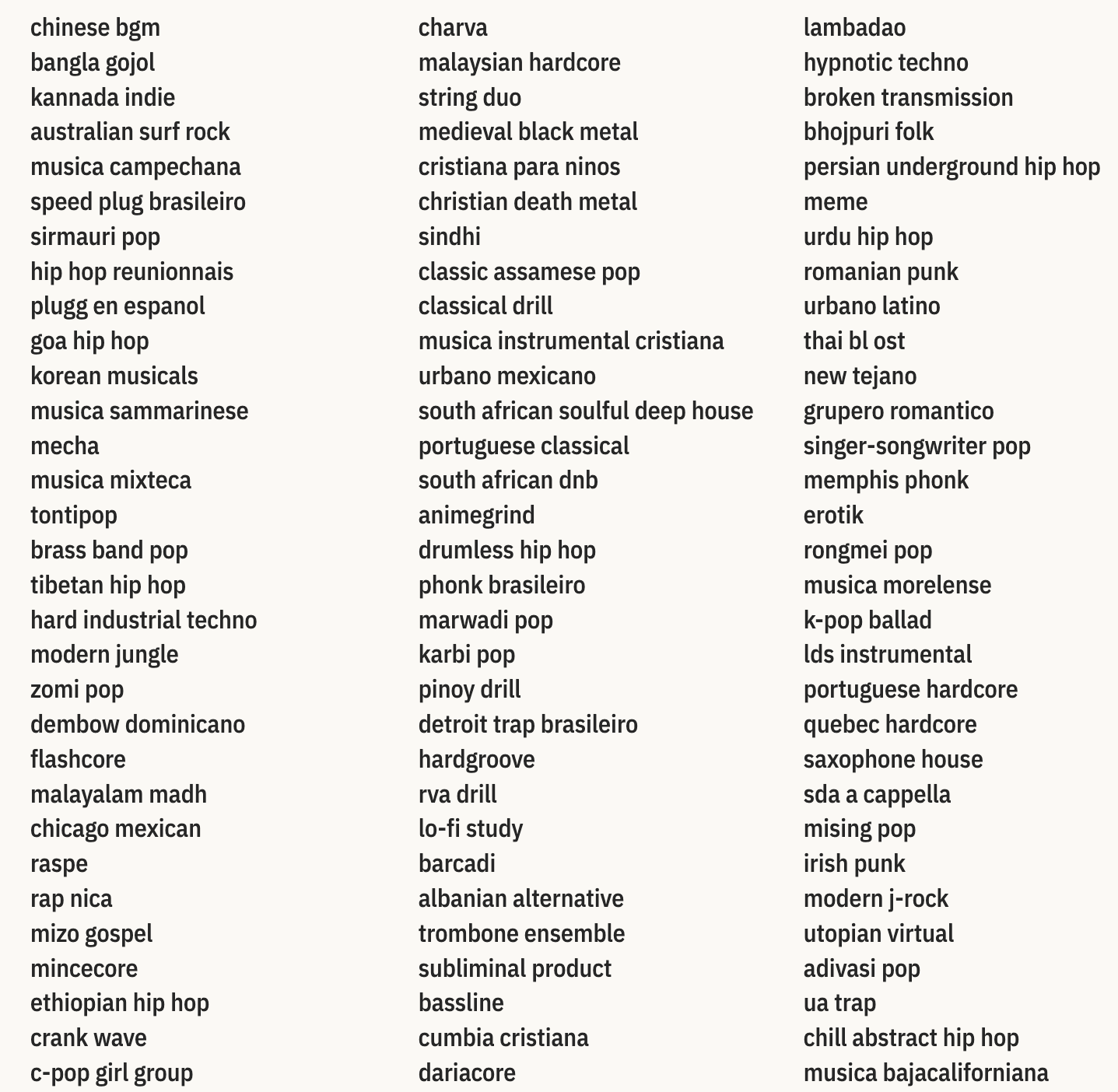

This was all fascinating, but I really perked up when the article began to share massive lists like a page of genres added to Spotify’s genre classifications in 2023. The screenshot below is merely an excerpt, but even in abridged form it evokes the staggeringly broad range of ways people are currently shaping sound, including everything from “modern jungle” to “christian death metal”; from “pinoy drill” to “memphis phonk”; from something called “broken transmission” to something called “dariacore”:

And finally, the essay links to a public Google Doc documenting 2,953 genres in Spotify’s system.

I have a lifelong love of music, and a longstanding interest in people doing things with enormous masses of sense-data, so this was a kind of powerful catnip for me. Looking at the Google Doc dataset was intoxicating, but I absolutely had to investigate further. I knew that some of the genres overlapped, and so I began to wonder whether someone had attempted to render it as a map, which might provide a comprehensible overview of all the genres in relational proximity to one another.

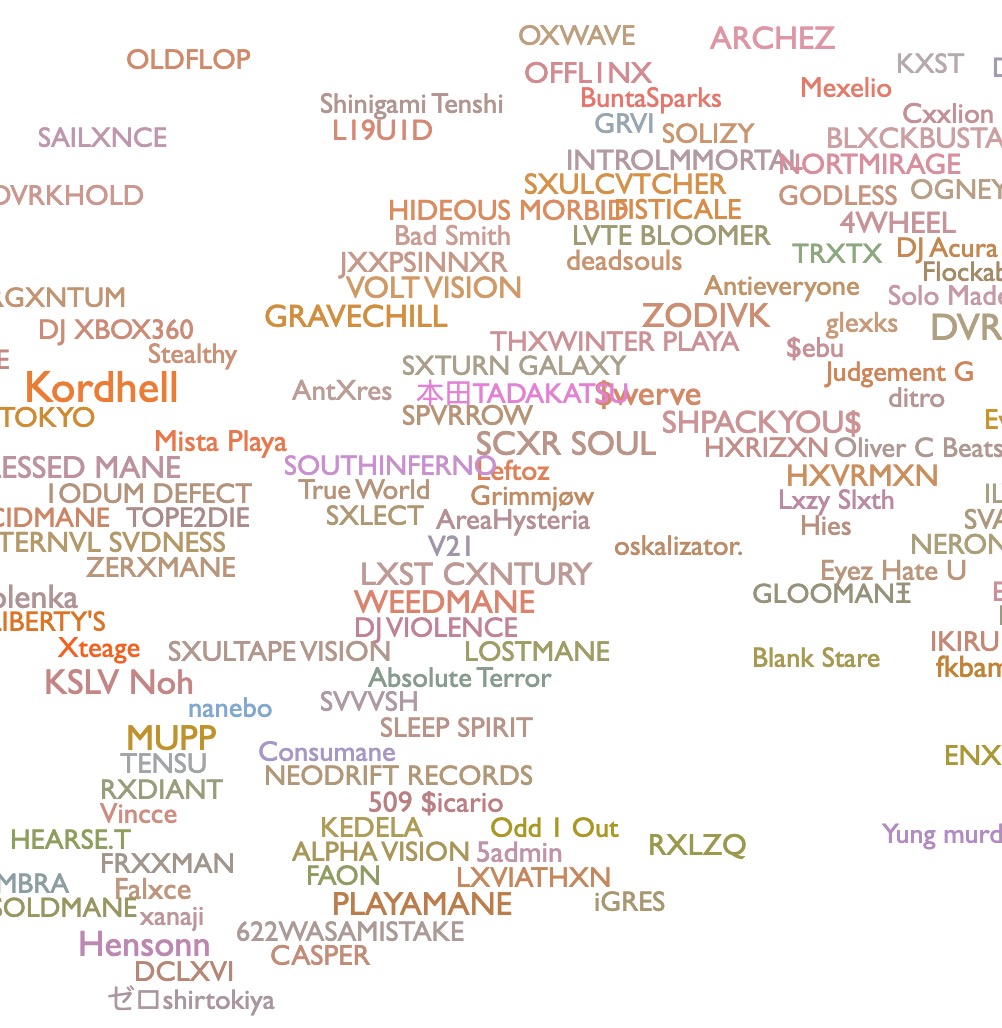

A little Googling led me quickly to Every Noise at Once, which provides exactly that. I can’t capture the whole thing in a screenshot, but here’s just one corner:

Computing Taste, Nick Seaver’s valuable book on music recommendation systems, describes this map as “a constantly shifting blob of genre names.” Seaver continues from there, giving us a brief tour:

In the spiky and electric northeast sat many varieties of house music—deep tech house, minimal tech house, acid house, Chicago house. Traveling south along the eastern coast (or, toward the “more organic”end of the island, on its “bouncier” side), one passed through a few global dance musics— Brazilian baile funk, Angolan kuduro, Caribbean reggaeton—before coming upon a deeply set bay dotted with national hip- hop variants (the analogous location in Madagascar is called Antongil Bay): Canadian hip- hop, Russian hip-hop, hip-hop Quebecois. Continuing south along Madagascar’s Highway 5, more “world music” genres appeared—Ghanaian highlife, Mexican norteño, Senegalese mbalax, Malagasy folk (the latter featuring Madagascar’s own Rakotozafy, a renowned player of Malagasy zithers).

In the spiky, organic southeast, the map broke apart, with a coastline of jazz- and blues- related genres looking out onto an archipelago of spoken- word recordings with labels like “poetry,” “guidance,” “oratory,” and “drama.” The dense and atmospheric western coast was dominated by various rock styles, from black sludge in the south to dark hardcore in the north. The two coasts were separated by a dense ridge of pop genres— ranging from Japanese Shibuya-kei to French yé-yé. From the bottom of the island extended a classical promontory, sedimented from an eclectic set of labels: “opera,” “Carnatic,” “polyphony,” “concert piano.”

Every Noise at Once is maintained by Glenn McDonald, who, until recently, served as Spotify’s “data alchemist.” Regardless of how you feel about Spotify, this “map” assuredly represents a remarkable navigational tool for anyone navigating the teeming oceanic ecosystem of contemporary recorded sound. There are innumerable ways to dig deeper into the data, but two immediately enticing things are: (1) you can click on any point in the map and instantly hear a representative sample of the genre, and (2) you can click on a tiny arrow and get a map of the artists associated with the genre. Here, for instance, is the cluster of artists that comes up for “drift phonk,” a genre, per Wikipedia, associated with social media videos of drifting street racing cars:

My curiosity fully activated, I reached out to contact Glenn. The following interview was conducted on December 21st.

One note: Glenn refers to “final updates” on the everynoise project, because he was laid off by Spotify on December 4. He asks for tolerance if he switches between past and present tense unpredictably: “The specific project to model genres this way may or may not continue at Spotify without me, I don't know. The cultural project belongs to music and isn't complete, so I think of it as potentially continuing in other forms.”

JPB: How many genres are listed on the master “every noise at once” map? Do you know exactly? The public dataset ends up just shy of 3,000.

GM: The code that generated the map also updated the description at the bottom of the page to dynamically include the count. As of what I assume will be the final update, it was 6,291.

And I know you've named a share of them, which is of interest to me, as someone who is often trying to find the “exact right word” for something. So of those 6,291, how many of them would you say you named?

GM: “Named” is a fuzzy distinction. Technically speaking, every genre name on the map was picked by one of the humans working on this project. Most of the time, that “picking” is just reflecting the existing name from the outside world.

Sometimes it is necessary to tweak a name to resolve real-world ambiguity. There are dozens of different scenes and movements that have referred to themselves as “indie pop” over time, for example. For this project they each need unique names.

Literally making up new names is an exception case, reserved for the times when listening patterns tell us that a community of artists and/or listeners exists, but that community hasn't come up with a name for itself. And even then, I would do my best to find a name that was derived from some observable aspect of the community or music.

Only when I failed miserably at that would I resort to making up a fanciful name of my own. “Escape Room” is an example of this last-resort that got a fair amount of press due to showing up in people's top genres in Spotify Wrapped the year I added it.

But there weren't many at that end of the continuum of invention. Tens, not hundreds.

Tens, not hundreds—and it sounds like you consider those instances something like “last resorts” rather than points of pride. But the stage where you're attempting to “derive it from an observable aspect” sounds like it might have occasionally yielded a “nailed it” feeling. Is there a genre in there that you or a colleague named by derivation where, at the end of the day, the process gave you a special sense of satisfaction?

I was always thrilled by every single addition. The joy of personal discovery, and of seeing the map of the world grow, was the same whether I was the one adding a genre or not, and whatever the source of the name. The name I invented that felt to me most like it would have been coined by somebody in NME was "Permanent Wave", for the music that was New Wave when it was new, except people are still listening to it decades later when it isn't, like U2 and REM.

One I like for more complicated reasons is “Slayer,” which I used for the genre of metal and aggressive metal-adjacent rock based around (usually) female voices. This is a play on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but also on the usage of “slay” as a superlative in metal, as seen in the name of the playlist that Heidi Shepherd (of Butcher Babies) maintains, “Heidi's Sisters That Slay Playlist.” And then, obviously, there's a very male metal band named Slayer, so I like the element of misdirection in using the name for a community that is in the same space as that band, but not.

I love both of these. In my own music collection I tag stuff like REM with “College Rock,” which, if I remember correctly, comes from Rolling Stone's old charts, but which captures something of that “out of time” quality. That music will always be “music I listened to in college,” even if it's not what college kids are listening to today, and even if the “college rock” chart doesn't itself even exist any longer.

So, if you had to point to a zone on the map that you think really demonstrates the value of this approach, where would you point to? When you show it to people for the first time, do you begin at the upper right or zero in on a particular spot? Is there a region which best showcases the ability to navigate tricky divisions with special nuance?

What you respond to in the map is really a function of your own knowledge and interests; I don't try to direct people. I consciously chose a rotation of the axes in which the top left corner, where you begin when you open the page, is sparse, so you only gradually realize the scope of the space as you begin to scroll.

I like the progression from "huh" to "oh" to "ohhhhh."

Yes, and then, at the very bottom, there's a pleasurable surprise—there's this battery of tools for exploration. I’ve played with most of the tools, and they're all really interesting. I know not all of these work any longer, but I was wondering if you wanted to hold up one or two of them for special consideration.

They're all fun, including the ones that are temporarily disabled and may never return, but Genres by Country is particularly informative, as it used the combination of genre/artist and artist/origin relationships in the underlying data to map genres to their homes automatically.

(Not) Every Label at Once is, I think, the last thing I added before the layoff: an application of the same logic as the genre map to record labels instead of genres. That was fun to work on because a) I like small labels with particular aesthetics, and b) the label data in the current music ecosystem is a gigantic free-text mess, so trying to make it more intelligible was an exercise in super-geeky regex normalization.

If we have time at the end I'll ask you about some of your favorite labels with particular aesthetics1. But first I wanted to pivot slightly, and forgive me if I take the long way around to this question.

No worries, I have coffee.

So far we have both been using geographic or cartographic metaphors for all this—like my questions talk about “exploring,” and we both refer to the everynoise “map.” But the thing that you’re “mapping” isn’t really a “space,” or—perhaps it's better to say that it’s a “computational space” rather than a “geographic space.” Nick Seaver’s book quotes you as calling it an “information-space-beast,” which meshes nicely with my understanding of what we’re thinking about.

This connects, in a sense, to the work of some contemporary geographers, like Aharon Kellerman, who have done work on mapping “the geography of information.” For Kellerman, this focuses not only on information’s movement across geographic boundaries, but also on information as an economic and commercial product more broadly, which seems like it might be adjacent to your project. But—and correct me if I’m wrong on this—you don’t consider yourself a “geographer,” I don’t think. I know you use “alchemist,” which I love, naturally—but I was trying to figure out if you came to this through computer science, or just plain old math.

Like it’s mathematical analysis that helps clusters of similarity to emerge, and then those are what get named in the naming process, if I have that right. Were you trained as a mathematician? As a computer scientist? Is it tacky to ask where you went to school?

Yes, functionally all this was done with math, and mostly pretty simple math.

The "map" is an XY scatter-plot with some fiddly code to bump the names around so there aren't all on top of each other.

The algorithms in the underlying genre system are done with database queries and counting and math, extrapolating from the human curation of representative examples.

I went to Harvard and majored in what Harvard calls “Visual and Environmental Studies,” which sounds like it’s kind of applicable to what I've been doing with music, but in practice I came to this through a career in software design, and my personal habit of poking at “music data” because music is the thing I love most.

But yes, as you say, math is a way of identifying clusters, and people have to look at them and understand what they actually signify in a human sense.

I didn't take any math or programming courses in college, but I also graduated in 1989, and the world was pretty different then. Most of the people my age who ended up in tech jobs at the time weren't CS or math majors, or at least that's how it seemed from what I knew.

Yeah, true. The fact that “humanities” people built a lot of the early Web and laid a lot of the groundwork for the 90s tech industry is something I'd like to see some historian do a deep dive on one day, and I wonder how much of our current “tech malaise” that many commentators have remarked upon comes from, well, these people leaving the industry and being replaced with STEM kids.

Regardless. I think all music lovers have an early memory of something that really makes them a music fan “for life”: some early discovery moment or maybe just a moment when a song just hits right. And if you have a moment like that that you want to talk about, I’d love to hear it. But I am also wondering if you have an early memory of something like that for software design, or poking at your music data. Were you homegrowing spreadsheets to track your CD collection or something like that?

Yes, exactly. My first job was doing tech support for Lotus 1-2-3, and my record collection was my own biggest spreadsheet. I always tell people that the way to get better at something is to really care about the results, because that forces you to learn whatever you have to learn to make them good.

Like, later, I got annoyed at the collation errors in the Village Voice Pazz & Jop music-critics poll, and learned about Levenshtein Distance (a technique for measuring spelling differences between words) in order to write some code for helping me fix them.

The single moment that I often talk about in origin-myth terms for me as a music fan was hearing the overdriven guitar in “Hold the Line” by Toto, and through that finding my way initially to metal. But I was addicted to music well before I became aware of that as any kind of choice.

And I've had those moments countless times since then, where I hear some tiny thing I didn't know about and it's like opening an unmarked door in a back hallway and discovering that there's a whole other world behind it.

You’re writing a book on this whole topic, which I am eagerly anticipating. On your blog you mention that the underlying argument of the book is that “streaming is good for music and streaming music is good for humanity.” Do you have a short version of that argument? I think I can see a hint of the argument when you talk about those “unmarked doors”—like having access to the world of music via streaming may make it easier to open the door, once you spot it, and go plunging through? But what else?

The book is mostly structured around fears and joys: understanding the fears that streaming provokes, and then explaining some of the joys that it makes possible. And yes, part of it is about access, and how that allows listening to be a direct exploration experience instead of an indirect shopping experience. But it's also about how streaming allows us, all, access to collective knowledge that wasn't collectable before.

Streaming can contribute towards all three of what I think of as the prime moral imperatives: towards joy away from misery, towards the distribution of power instead of the centralization of it, and towards better understanding of moral consequences. But all of those are complicated and we're still barely at the beginning of whatever this new era is going to become.

It's that kind of book: seeking love inside complexity, as opposed to bullet points about how to get ahead.

Very much my kind of read. And I appreciate the way you talk about separating “listening” from “shopping” here. But if I'm to zero in on the “fears” side for just a moment, I have to be honest and say that I also know that a lot of musicians are concerned about the decline in record sales, which many of them rely on as a prime source of revenue. A lot of musicians I talk to see streaming services as offering a kind of devil’s bargain, at best. Now, I love using Spotify—and your map—for discovery purposes, but I also still try to buy music as often as possible. I buy MP3s through Bandcamp, and, heck, I still bought CDs in the year of our lord 2023. But with each year this feels more and more like a niche pursuit—and I worry that that can't be healthy for the overall music ecosystem. I don't want to put you in the position of being an apologist for the industry, but I will ask whether you think ownership of music—shopping for music—is an outdated paradigm.

Basically, yes. I was an absurd overbuyer of CDs for decades, so I have as much literally invested in that model as anybody, but yeah. I think streaming beats hoarding, both individually and collectively.

The revenue questions are more complicated, and I talk about them in several ways in the book, but the basic truth is that streaming is on track to bring the recorded-music industry back to about the same overall value it had at its peak, and that value is distributed a little more broadly now than it was in previous eras.

Anything you do to direct more money to people who make music is incrementally good. Buying CDs, going to shows, buying hats and T-shirts. But systemically speaking, buying CDs is not a real plan for the future.

If we want more people to be able to make a living making music (and it's a complicated question what “more” means there), we need to find ways to get a lot more money flowing towards them. Higher-priced streaming subscriptions might be part of this. But also other kinds of ways to express and reward and build fandom. The book does not contain magic solutions to this.

I have followed Damon Krukowski's argument for a “penny per stream” with some interest, though I haven't seen it go anywhere in the last few years, so I don't think it's an especially likely outcome.

No, that totally misunderstands how royalties work.

And I think part of the reason why I have begun doing these interviews is as a way to think about different ways to express my own fandom for people with weird and interesting projects, and maybe a way to contribute to my own little corner of the ecosystem.

That's a great motivation.

A few quick final questions. Did you listen to music while we were talking? What's on? (I've been listening to a long Éliane Radigue drone.)

The core of my listening works by making a big playlist of new releases I'm maybe interested in every Friday, and then cycling through it seeing what I turn out to love as the week goes. This week's is here:

The death of New Releases by Genre on everynoise affects me as much as anybody, and I have to think hard now about how to find new bands I'm not already following without the tools I had and made.

That was a blow to me as well; I had only about two weeks to play with it before it was gone.

I just hit the final song on that playlist, so I was listening to the last two hours of it during these two hours.

Very nice. And I've looked at a few other playlists that track your listening in a pretty fine-grained manner, so instead of closing on music I thought I'd close by asking what you're reading right now.

I just finished Kirsten Kaschock's really thought-provoking extreme novel Sleight, about the people in and around a fictional alternative performance art. From that I'm snapping back across contexts to Absolutely on Music, Haruki Murakami's book of conversations about classical music with Seiji Ozawa.

Sort of totally different, and yet sort of orbiting the same suns.

Absolutely. Thanks again for sitting with me for a spell.

I still have reservations about whether Spotify, broadly speaking, is good or bad for music at the end of the day, even after speaking with Glenn. But I do feel certain that the tech industry loses something when it fails to honor and elevate its curious humanists, when a company like Spotify jettisons someone like Glenn. I’d write a polemic here lamenting the way capitalist enterprises shortsightedly shed their “anomalous contributors” in favor of “well-organized unit[s] in a well-organized organization,” except Glenn has already done this more eloquently than I can.

I send this at the end of the year, which is a time for end-of-the-year lists (although Elena Gorfinkel’s “Against Lists” serves as a compelling counter to this argument, and is worth a read). What follows is not quite a top ten, but it is a collection of some 2023 albums that I deeply enjoyed spending time with, along with links to buy if you are so inclined:

- Between, Low Flying Owls (12K)

- Deathprod, Compositions (Smalltown Supersound)

- Éliane Radigue with Charles Curtis, Naldjorlak (Saltern)

- Kali Malone, Stephen O’Malley & Lucy Railton, Does Spring Hide Its Joy (Ideologic Organ)

- M. Sage, Paradise Crick (RVNG)M. Sage & Zander Raymond, Parayellowgram (Moon Glyph)

- Philip Jeck & Chris Watson, Oxmardyke (Touch)

- Tongue Depressor & John McCowen, Blame Tuning (Full Spectrum)

- Tujiko Noriko, Crépuscule I & II (Editions Mego)

—JPB, writing from Cape May, NJ on Wednesday, Dec 27

I forgot to do this. ↩

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)