Wednesday Investigation 09: Gerhard Richter, Andrea Fraser, and Capitalist Realism

On the status of painting under capitalism, Andrea Fraser's fake tour of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and how "scientific philanthropists" hobbled the welfare state at the turn of the twentieth century

I wanted to look, this week, at the work of Gerhard Richter. Richter is probably one of the most important artists of the last fifty years, but I don't know that much about him. (For a long time I knew him primarily as the guy who did the painting that became the album art for Sonic Youth's Daydream Nation.) I wonder if he's fallen into a blind spot, for me, because he's best known as a painter--my knowledge of contemporary painters is frankly underdeveloped.

Part of the reason for this, I think, is that, like many people, I was taught art history--especially the history of painting--as a series of movements or "schools." You have the Impressionists, then the Post-Impressionists, then the Expressionists and Fauves and Symbolists, then the Futurists and Surrealists, then the Abstract Expressionists and Pop Art... The inadequacies of this model become ever clearer once you get beyond, say, 1970: at around that point, painting appears to flare out into a profusion of diffuse "Post-" movements--Post-Minimalist, Post-Conceptual--and no movement from that point on ever quite seems dominant enough to explain everything that's happening. This is maybe how you get people giving up entirely on trying to synthesize the moment and instead just releasing books called, like, New Perspectives in Painting, with a cover where each painting just inhabits its own isolated blob:

Richter's work can't be positioned easily even within a particular subzone of this fractured "Post-everything" space. He's well-known for his "blur" paintings, which could be considered part of the (Post-Pop) Photorealist school; his "color chart" paintings read as Post-Conceptual; his Grey Paintings, Post-Minimalist. (A major retrospective of his work, currently at the Met, gestures slyly at all this Post-ness in its title: it's called Painting After All.)

If you're looking for a clue, though, you could look at how Richter once categorized himself. This was decades ago, so I don't know if Richter still identifies this way, but he once threw in with a German school of painting, founded by Sigmar Polke, called "Capitalist Realism," which emphasized the "commodity nature" of Post-War and contemporary art. For what it's worth, Richter is still identified as a Capitalist Realist on his Wikipedia page:

Google "capitalist realism" and one thing that comes up is this book by cultural critic Mark Fisher. I've seen this book before, but I must confess: even though I admire Fisher's work I've avoided this particular volume--its vision of capitalism as an all-pervasive ideology to which no coherent alternative can even be conceptualized leads me to believe that this book is going to be a uniquely bleak entry in the already pretty bleak field of anti-capitalist writing. (My aversion here is undoubtedly compounded by the sad fact that Fisher took his own life in 2017.) I did poke around in some brief summaries of the book this week, though, and it seems that it doesn't directly pick up the gauntlet thrown by Polke--it focuses more on film and fiction than on art specifically.

But there's no shortage of other writers and thinkers who have engaged the question of the ways artworks are ever more deeply enmeshed in a system for the buying and selling of commodities. One of the most important of these writers, Andrea Fraser, has an outlook no sunnier than Fisher's--she writes "[w]e are living through a historical tragedy: the extinguishing of the field of art as a site of resistance to the logic, values, and power of the market"--but she's well worth checking out if you're trying to figure out, specifically, what's going on in the world of painting nowadays. Her collection Museum Highlights proposes a potent alternative to the "schools and movements" model: specifically, she encourages us to start thinking of artworks as "pure instruments of financial investment," which honestly strikes me as a more useful means of understanding the last fifty years of painting--and, indeed, art in general--than the increasingly-outdated "schools" model.

I'm not alone in thinking this: Fraser's whomping, 900-page book from a few years back, 2016: In Museums, Money, and Politics, is a sort of capitalist cartography of the art world--it's essentially a giant directory of political donations made by museum trustees--and it was considered to have enough explanatory utility to be named the single best book of art criticism of the decade by ARTnews (who have been in the business, so to speak, since 1902). Interestingly, ARTnews describes the book as not only a work of criticism but as a "research-based artwork" in its own right (and the book makes the case for its own commodity status with its $125 list price).

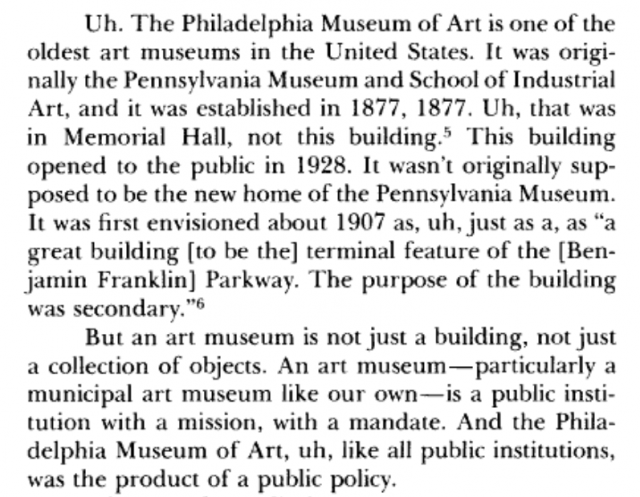

This isn't merely interpretive reach. Indeed, Fraser's work has long blurred the lines between criticism and art: all the way back in 1989 she developed a performance piece, "Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk," where she posed as a fictional docent, Jane Castelton, and led visitors around the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in which she largely ignored the artworks, remarking instead on infrastructural aspects of the building (water fountains, restrooms). Here she is in the building's cafeteria:

But Castelton's speech wasn't just restricted to pointing out aspects of the building that generally go unseen. More interestingly, she allowed her talk to drift into historical asides about the function of museums in general.

To explore the nature of that public policy, Fraser/Castelton's talk incorporated lengthy passages taken from historical documents written by nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century "bourgeois charity organizers" and "scientific philanthropists." Taken collectively, these passages reveal the ideological project that the founders of museums saw themselves as undertaking. Specifically, they were explicitly designing museums to serve as part of a system of "incentives and disincentives, goads and deterrences" intended to reform character defects of the poor, as part of a larger program of denying them more material forms of public assistance. Give a person a fish and they'll eat for a day, give a person access to a painting of a fish and as a newly cultured subject they'll raise themselves from their state of indolence and [eventually] eat forever? Something like that.

So we've moved from "why is painting the way it is" all the way to "why is the welfare state the way it is"--which is all fascinating stuff, for my money, even though it's led me a bit far from Richter. And I'm not actually any closer to investigating what I originally set out to investigate this week: my notecard index asked me to look specifically into Richter's complex collage or "archive" work, Atlas, and a similar work, Kulturgeschichte [1880-1983] from his contemporary, Hanne Darboven. I still want to do that, so that's where we'll pick up next week.

Oh, and, while we're on the topic of "coming attractions": I recently found myself in possession of a huge trove of around, uh [checks notes] 1,300 different video games, which will form the basis of a future installment of this newsletter. Here's the backstory: like many of you, I've been busy, over these past few weeks, donating money to anti-racist causes, as well as making purchases of various things from various creators who have pledged to donate the proceeds toward social justice ends. One notable offering emerged in the indie video game community, where hundreds of game creators came together, in a stunning show of industry solidarity, and agreed to have their games included in a "bundle"--the Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality. At the end of the the day, this bundle came to include somewhere around $9,500 worth of video games, made available for a $5 (minimum) donation, with all proceeds split between the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Community Bail Fund. They ended up earning over eight million dollars.

A number of people have made attempts to find the unique and surprising gems in this bundle, and I'll be doing the same, but even a cursory dip into a pool of this size is going to take a couple of weeks. Stay tuned, friends.

-JPB, Dedham, MA, June 16 // (revised Wednesday, June 17)

PS: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org--an online bookstore with a mission "to financially support local, independent bookstores"--and I maintain a list of books referenced in this newsletter. FTC rules advise me to disclose that I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)