Wednesday Investigation 08: Longevity, responsibility, and Inadvertent Human Intrusion

On the Long Now Foundation, Jeff Bezos' obscene accumulation of wealth, and the Landscape of Thorns

For the past two weeks, we have witnessed a remarkable series of protests and activist actions, marked by frankly astonishing levels of passion, intelligence, ambition, and efficacy. These actions are now entering their third week, and their staying power is also proving remarkable: a headlining piece in the New York Times today reads "Other Protests Flare and Fade. Why This Movement Already Seems Different." A meme on Twitter is quick to remind us, however, that the history of civil rights activism in America has no shortage of campaigns that have been distinguished by their longevity: the Birmingham movement led by Martin Luther King, for instance, ran for 37 days (April 3 – May 10, 1963); the Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted over a year (December 5, 1955 – December 20, 1956).

Last week, I considered investigating some of the resources referenced on this hyperlinked syllabus about an organization called the Long Now Foundation. At the time, I demurred: the activist spirit in the air made it feel more appropriate to focus on "insurrectionary time," materials that pointed us toward the liberatory potential of unknown futures. That activist spirit has in no way been dispelled, but I think that both the Times piece and the Twitter meme reflect, in different ways, that the conversation has turned (at least in part) to the future of these actions, and the question of what enables an activist movement to persist through time. So I think there may be something to be gained from turning our attention to the practice of long-term thinking, to see what it might teach us about the persistence (or ephemerality) of the social, political, ideological, and/or material things that comprise our world.

The Long Now Foundation is led by engineer and inventor Danny Hillis and writer and editor Stewart Brand. Some of you may know Brand as the author of How Buildings Learn, a widely beloved book of architectural criticism (it was adapted by the BBC into a six-part miniseries, which you can watch on YouTube). Others of you may know Brand because of his early involvement with the New Games Foundation, an organization devoted to promoting cheap, improvisational, inclusive opportunities for physical play. He may be best known, though, as the editor who put together the Whole Earth Catalog, an "an evaluation and access device" that provided vendor information for items that were "[r]elevant to independent education," and "[e]asily available by mail." Their 1972 issue, billed as The Last Whole Earth Catalog, also maintained a list of "suggested reading," and an anthology complied wholly of material sourced from books on that suggested reading list was compiled by a counterculture historian just a few years ago.

(That 1972 issue wasn't really the last issue, by the way--there were several others, all the way up to a Millennium Whole Earth Catalog in 1994 and a 30th anniversary reprint, essentially a last gasp, which appeared in 1998. It's perhaps unsurprising that the catalog went into decline right around the advent of the Web--as anyone who hasn't used the Yellow Pages recently can tell you, big compendiums of resources just feel less useful in the age of the search engine. With that said, if any of you are reading this and find yourself waxing nostalgic, or even just thinking that there may still be room, even in our information-saturated era, for a carefully curated list of useful tools, you could check out Wired editor Kevin Kelly's blog or this book by him, both of which strike me as undisguised attempts to carry the Whole Earth ethos forward into the 21st century.)

But back to the Foundation. Brand, Hillis, and others founded the Long Now Foundation in 1996, with the intention of encouraging the practice of long-term thinking, specifically urging us to consider forms of human endeavor that might be meaningful on a scale measured in 10,000-year intervals. Where something like Charles and Ray Eames' famous short film, Powers of Ten (included in the Long Now syllabus) asks us to dramatically expand our sense of scale as it pertains to space, the Long Now asks us to do a similar expansion as it pertains to time. They have organized a variety of projects to promote this idea, they have set up an ongoing series of seminars, and, for some reason, they also run a bar.

Perhaps their most provocative project, however, is Hillis' invention, the Clock of the Long Now, a technological device designed to last 10,000 years. Hillis, in 1993, proposed it this way: "I would like to propose a large (think Stonehenge) mechanical clock, powered by seasonal temperature changes. It ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium." Trying to design for a 10,000-year timescale undeniably invites some fascinating questions, which lead to intriguing answers.

Interestingly, very similar questions have also been confronted by radioactive waste disposal experts, who have also needed to consider the problem of how to create, say, warning signage that will still be meaningfully legible to a future civilization. To get some sense of just one of the difficulties involved, remember that, with the possible exception of Euskara (Basque), we know of no human language that has remained in continuous use for 10,000 years--Persian, Arabic, Greek, and Old Chinese all clock in somewhere around 2000-3000 years.

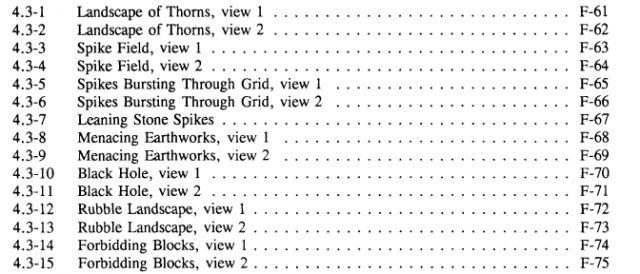

Our syllabus digs into the attempt to solve this problem. It includes this 1993 document, "Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant," which documents the absolutely fascinating work undertaken by multidisciplinary panels "spanning the fields of materials science, climatology, communications, and the social sciences including archaeology, anthropology, and psychology" as they attempt to design methods for communicating with a future culture that "may not be directly descended from our own." One team on the project starts to think about how to design a zone that would deter people from traversing it, that would appear to have no "adaptive value." They think about how to fill an area with signs that will convey "danger to the body; darkness; fear of the beast; pattern breaking chaos and loss-of-control; dark forces emanating from within; the void or abyss; rejection of inhabitation; parched, poisoned and plagued land," etc. In effect they are designing a nightmare-scape:

Yikes:

This same team is responsible for producing a now notorious block of warning text, which reads like a dystopian poem. It begins:

"This place is a message, and part of a system of messages. Pay attention to it! Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture. This place is not a place of honor... no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here... nothing valued is here."

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant began receiving nuclear waste in southeastern New Mexico in 1999 (the final plan for how it will be future-proofed is not expected to be complete until 2028). Also in 1999, the prototype of the Clock of the Long Now was completed (it began to tick on December 31, 1999). Stewart Brand's book on the Clock, subtitled Time and Responsibility, was published a few months later.

There have been a few changes to the plan over the years--instead of a once-per-millennium cuckoo, Hillis and musician Brian Eno have designed a set of ten chimes, designed to ring periodically, progressing through an algorithmic sequence of 3.5 million permutations which will not repeat for 10,000 years.

I think that's all pretty cool, although I have some concerns about the Long Now project more generally. In its belief that humans can act meaningfully on a 10,000 year scale, the Long Now Foundation appears optimistic--especially in contrast to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant planning team, which has its thinking guided by a dispiriting assumption that entire cultures will likely be swept into ruin over such a vast span of time. But--well--we talked last week about the distinction between optimism and hope, and while the Long Now seems optimistic about our ability to extend life as we know it into the future, there's a way in which it seems to avoid expressing hope that the unknown future might be a site of positive transformation.

Brand, Hillis, Kevin Kelly, Brian Eno--they're all white male baby boomers, who lived meaningful lives in affluent cities, and they seem afflicted with a touch of that baby boomer myopia, like they have a hidden belief that they're somehow the last generation to matter. Seen through that lens, their future-oriented mindset can look like just more baby boomer ego: they seem to hope mostly to keep the party going for another millennium, or to sign their names at the vastest imaginable scale. Long-term thinking can be harnessed for progressive purposes--such as if you're designing an action plan to keep an activist movement alive--but it can also be harnessed strategically by repressive agents and capitalists, who have nothing if not a vested interest in seeing the status quo persist. I can't think of a better symbol for this beyond the fact that the Clock is currently being built on Texas property owned by Jeff Bezos, who became history's first centi-billionaire in 2017. (If you want an additional experiment in expanding your sense of scale, check out this nauseating visualization of Bezos' wealth and tell me, when you're through, that you don't find yourself praying for the arrival of the obliterating finger of time.)

More happily, there is a secondary Clock site in Nevada, on land adjacent to the Great Basin National Park, purchased away from a mining company, and chosen, in part, for its proximity to an ancient bristlecone pine forest. Bristlecone pines are the oldest known living non-clonal organisms on Earth, with some of them more than five millennia old.

--JPB // Dedham, MA, June 8-9 (revised Wednesday, June 10)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)