Wednesday Investigation 06: Symbaroum, cultural beings, and monstrous compendiums

On monstrous compendiums, Scandanavian role playing games, indie cartoonist Mat Brinkman, Tolkien’s orcs, and the moral beliefs of fantasy creatures

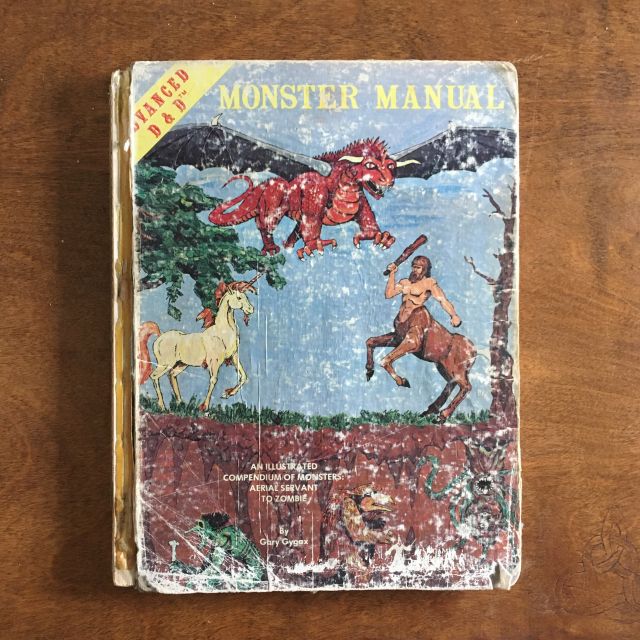

When I was around eight years old, I received a copy of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual ("An Illustrated Compendium of Monsters: Aerial Servant to Zombie"). Aside from a couple of early childhood classics (shout out to Goodnight Moon) this is probably the book I have had in my continuous possession for longer than any other, and it comes off the shelf with surprising frequency, despite the fact that I'm not currently running a role-playing campaign. My copy certainly shows signs of four decades of continuous wear and tear:

There are lots of little details in this book that I would love to discuss individually. I could almost go through page by page, pointing out the good, the bad, and the weird--there are plenty of all three. (Doing so would also complete an informal trilogy of me writing about old-school Dungeons and Dragons books: I wrote about the Dungeon Masters Guide as part of this thing I wrote for Tor.com, and I wrote about the AD&D mythology sourcebook Deities and Demigods as part of this thing I wrote for the Melville House blog.) But it's not really in the investigative spirit to lavish attention on a book I already know so deeply. I bring it up only to explain that my young obsession with it, taken along with my young obsession with syndicated reruns of Tsuburaya Productions' Ultraman, instilled in me a lifelong love of monsters, and an abiding belief that the design and effective deployment of monsters is a legitimate realm of aesthetic expression. (Both of my published novels have monsters in them, and we're not talking in the metaphorical sense.)

So when some interesting-looking monster design crosses my radar, the compulsion to investigate awakens. Back in 2015 I stumbled upon Cave Evil, a game of "necro-demonic warfare" featuring monster design by the experimental comics artist Mat Brinkman (among others). With monsters like the Rotten Shape and the Bat Web, I was pretty intrigued, but I balked at the $90 price and never scored a copy (the game is now a collector's item, and the cheapest one I could find as of this writing is going for about $380.) I did manage to score a copy, last year, of Teratoid Heights, a wonderful book-length dive into Brinkman's monster-riddled subterranean environments:

So, sure: if you're looking for monsters, representations of them are easy enough to find, but finding a bunch of them together, in a monstrous compendium--like the Monster Manual? That's more rare, and so good compendiums have a special spot in my heart. They're mostly associated with games, though not always--a notable one that undeniably reads like game lore but which doesn't have a connection to any real-life game is this publication (free PDF!) from artist Jordan Speer, an "incomplete guide to the many fiends of the subterranean mud maze ZUG." What a joy:

But let's not stray too far from the topic of monsters in games. A few years back, I made a note to investigate a Swedish role-playing game, Symbaroum, which, at the time, had newly been translated into English. Somebody on Twitter recommended it as a cross between the work of monster-loving filmmaker Guillermo del Toro and the notorious grimdark tabletop game Warhammer. "Pan's Labyrinth monsters in a fantasy setting," they wrote. "All 30 foot eyeless forest gods and skull-headed deer."

30 foot eyeless forest gods are definitely my jam, and with this newsletter in mind I went poking around looking for more. I don't have the main book of Symbaroum rules, available here as an affordable PDF, but I saw that they also had, lo and behold, a Monster Codex, and since it was the monsters that had lured me this way in the first place, that's what I first chose to grab.

This cost me about twenty bucks, but there's loads of cool stuff in there, drenched in a thick layer of absolutely wonderful Scandinavian gloom. There's a carnivorous willow tree worshipped by an evil cult, and there's a fist-sized tick that tries to crawl into your throat. You can fight a "huge and wobbling" toad or you can fight this thing, the "Gwann," that looks like a gigantic star-nosed mole:

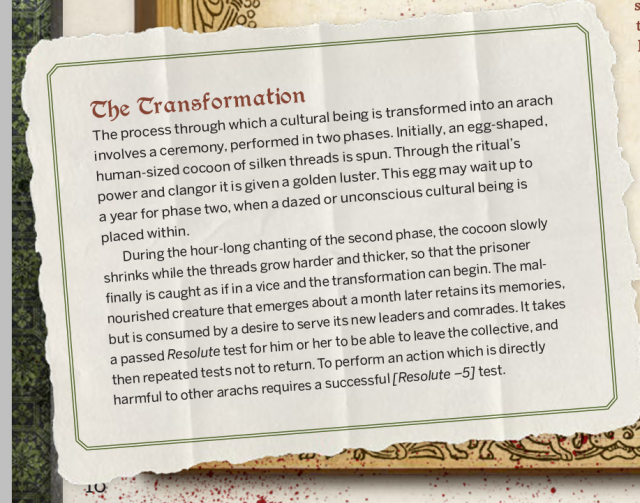

Then there are the "Arachs," humans that have been transformed into seven-jointed, four-eyed spider beings... oh, wait, no, it's not strictly humans... it could be, what, any humanoid?

Wait, no, it's "cultural beings?"

"Cultural being" was an unusual enough phrase that I dug a little deeper into how the game was using it. In the third part of the Codex there's a six-part categorization scheme for the game's monsters: Abominations (basically demonic creatures), Beasts (monstrous animals), Undead (zombies, ghosts, etc), Flora (what it sounds like), Phenomena ("hateful place[s]"; "climate condition[s]"; "contagious states of mind"), and... Cultural Beings, the game's category for "intelligent, community building creatures."

Symbaroum, interestingly, seems to err on the side of generous inclusion with regard to who gets counted as a Cultural Being. The description explicitly indicates that this grouping includes "humans, elves, bestiaals [animal-headed shapeshifters], changelings, ogres, goblins, darklings [a sort of nocturnal amphibian], and trolls." Even more interestingly, players can choose from to play the game as an emissary of nearly all of these being-types: the game's core rulebook allows you to play as a human, a changeling, an ogre, or a goblin, and a later player's guidebook allows for you to play as an elf or a troll, among others; the Codex itself provides rules for playing as a bestiaal.

This stood out to me, in part, because it's pretty different from Dungeons and Dragons. Dungeons and Dragons famously assigns each monster a moral alignment: goblins, in my Monster Manual, are designated "lawful evil," and ogres and trolls "chaotic evil"; elves, by contrast, are designated "chaotic good." Once these camps are set up, D&D steers players toward playing the "good" creatures, and prohibits them from playing the "evil" ones.

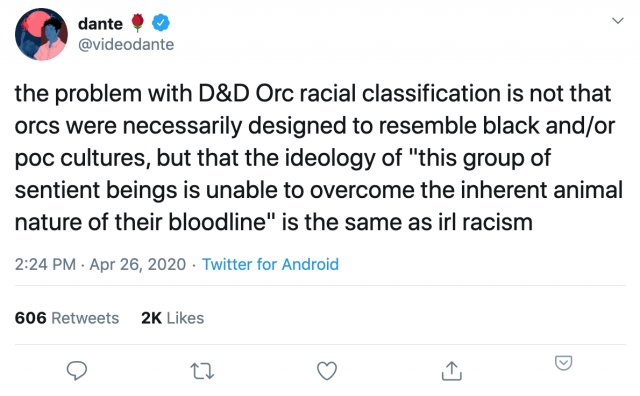

Dungeons and Dragons has come under some scrutiny, recently, for advancing this notion that entire subgroups of sentient beings--D&D, perhaps ill-advisedly, uses the term "races"--could be meaningfully described as "evil" (bloodthirsty, unintelligent, etc.) Unfortunately, this idea is baked rather deeply in to the very genre of epic fantasy itself: consider, for instance, J. R. R. Tolkien's figure of the orc, a creature presented as being uniformly malevolent. (The question of whether Tolkien really believed that there were entire cultures beyond the reach of moral redemption, and, perhaps more importantly, whether this belief was charged with racist baggage has been hotly debated for some time now--it even has its own section on the Wikipedia page for "Orc.")

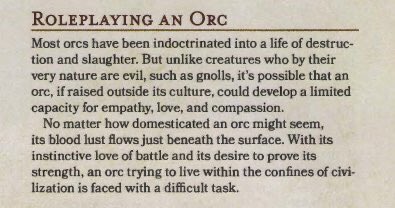

Regardless of what Tolkien was or wasn't saying, it's clear that Dungeons and Dragons operates under the belief that creatures are inherently good or bad: I mean, the alignments are printed right there in the books. They have received some push-back on this in recent years, which has led them to have temper their more recent descriptions of the orc, but even the tempered versions are... well, let's take a look. (This is from Volo's Guide to Monsters, an official Dungeons and Dragons supplement from 2016.)

On April 25, Quinn Welsh-Wilson, pointed out this passage on Twitter as an instance of "blatant racism," kicking off a messy discussion. I'll spare you the full recap, but you can likely imagine the general shape of the battle lines. At first, digging down into it made me want to strike a weary pose--who isn't weary, these days, of having to fight in the ongoing culture war? But I honestly find it heartening to see groups of young people deeply considering the question of in how representations of intelligent beings in fantasy could be improved, searching for ways to keep them from aligning with or reaffirming the worst of our human impulses.

And I'm heartened, ultimately, by the choices that Symbaroum has made with regard to this problem. Symbaroum doesn't have any orcs in it, but they've made the choice to chart what's clearly an alternate path with regard to their "sentient beings," bypassing the assignation of inherent moral qualities entirely. I think that's admirable. They go so far as to problematize the use of the term "monster" even for non-cultural beings: of the Blight Worm (an "Abomination"), they write "That a town guard [...] or a wilderness guide [...] calls the Blight Worm a monster is only to be expected. But do not forget that the Blight Worm, according to its own bestial logic, probably regards explorers and others who encroach on its territory as monstrous intruders; enemies who must be fought, driven off, or preferably destroyed."

I'm not saying "even Abominations have a coherent ethics" could serve as the slogan undergirding a radical approach to the Other, but... I'm not not saying that, either.

A final note: midway through my process of writing this post, a brand new monstrous compendium fortuitously flitted across my Twitter timeline: Ekphrastic Beasts, edited by Boston-area poet Janaka Stucky, who also runs the indie press Black Ocean, home to poets like Nathaniel Mackey, Elisa Gabbert, and Aase Berg. Ekphrastic Beasts is in the final stages of its Kickstarter campaign, but if you're interested, you can still back the project up until Thursday, May 28. Tomorrow!

-JPB, Dedham, MA // May 25-6 (revised Wednesday, May 27)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)