Wednesday Investigation 04: The ecosystem maps of Helen and Newton Harrison

"The Harrisons have done dozens of projects, many of which also strive to undo the 'arbitrary divides' that prevent us from visualizing the contiguous megastructures of the natural world."

My earliest "investigate" note on the Harrisons (Helen Meyer Harrison and Newton Harrison) didn't look too promising: it merely noted their involvement in "political art action" and supplied an accompanying URL--dragon.co.uk--that long ago stopped pointing to their work. But something else popped up in my note index when I ran a search on them: their affiliation with an odd journal called New Wilderness Letter.

New Wilderness Letter was edited by Jerome Rothenberg, a poet who is possibly best known for editing Technicians of the Sacred, an influential anthology of poetry drawn from the indigenous traditions of Africa, America, Asia, Europe and Oceania. Rothenberg explains (in his remarks on the occasion of the book's 50th anniversary edition) that Technicians was intended, in part, to bring to light traditions that were "brutally repressed," that had been dismissed as "primitive" or "archaic." They were, Rothenberg explains, "in no sense inferior to what we sought or created as poetry in our own time and finally in no sense inferior to what had been delivered as the poetry and poetics of the normative 'canonical' past. Furthermore they provided rich new contexts for poetry—not as literature per se but as a means, both public and private, for experiencing and comprehending the world."

After Technicians, Rothenberg continues to explore his belief that poetry could alter our experience of the world; that it could, in effect, expand our consciousness. He edits an ethnopoetics journal called Alcheringa for a decade--collecting "songs, chants, prayers, visions and dreams, sacred narratives, fictional narratives, histories, ritual scenarios, praises, namings, word games, riddles, proverbs, sermons"--but toward the end of that run he starts up New Wilderness Letter, a project which seeks to explore the esoteric fringes of poetry, seeking work that deals with the consciousness-expanding potential "of numbers, of dreams, of signs." The magazine ran for twelve issues (1977–1984), and, with such a mission, it is perhaps unsurprising that the magazine attracted an eclectic group of people to its editorial board: not only boundary-pushing poets (Donald Antin, Steve McCaffery, Jackson Mac Low), but also early performance artists (Eleanor Antin, Allan Kaprow), experimental musicians (Pauline Oliveros), and, lo and behold, Helen and Newton Harrison, doing... well, whatever it is they're doing.

So what are they doing? It's probably best to think of them as cartographers, although they're a uniquely imaginative set of cartographers. (They were, in fact, the first recipients of something called the Corlis Benefideo Award for Imaginative Cartography.) They embellish their cartographic work with techniques taken from a wide array of other disciplines: painting, photography, poetry, performance... well, perhaps it's best to take a look at an example. Let's dip into the piece they contributed to a 1979 issue of New Wilderness Letter, "Two Meditations, Two Commentaries & Eight Questions on the Great Lakes of North America."

Structured as a dialogue, it opens with Newton: "We were invited to the city of Milwaukee to do a work on the Great Lakes. Our normal way to begin a work is to investigate."

(I like this so far, go figure.)

Newton continues: "[W]e began by walking the halls of the institution and then the streets of the city, telling people we were strangers, naive and curious, and asking why we could not drink the water (directly from the lake) and could not eat the fish."

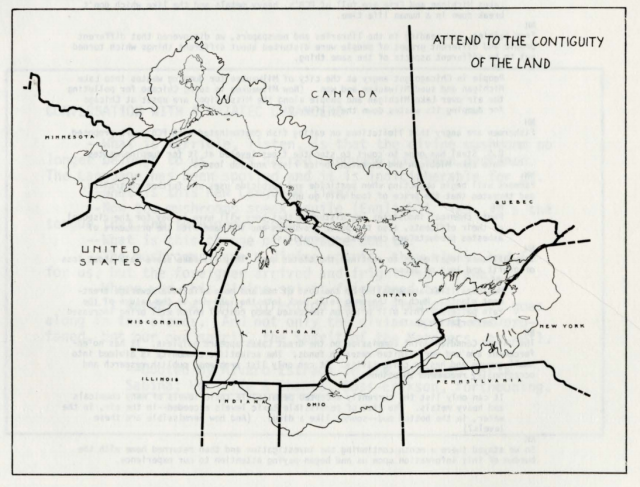

Then Helen takes over: "We had the problem of informing ourselves, to find out what every schoolchild who lives there knows. For example, the Great Lakes are a single system, formed by the last glaciation 10,000 years ago, whose water flows from Lakes Superior to Huron and Michigan, to Erie and Ontario and out through the Saint Lawrence River to the Atlantic. They have a total water surface of 94,680 square miles[,] and a total watershed area--land and water--of 295,800 square miles."

In that passage, the phrase that perhaps showcases the Harrison's approach to their cartographic art and environmental activism is "a single system." They embrace holistic thinking, emphasizing and visualizing contiguities and continuities in their work wherever possible. We can see this as their Great Lakes discourse turns to look more deeply at the issues of pollutants in the lakes: "From talking, and reading in the libraries and newspapers, we discovered that different people and different groups of people were disturbed about different things which turned out to be different aspects of the same thing."

They gathered information about the situation, and then "returned home, with the burden of this information upon us and began paying attention to our experience." This concludes the "First Commentary."

Later, in the "Second Commentary," they write about their return to Milwaukee, whereupon they "implored the citizens to give up at least one bad habit. 'What bad habit?' they asked."

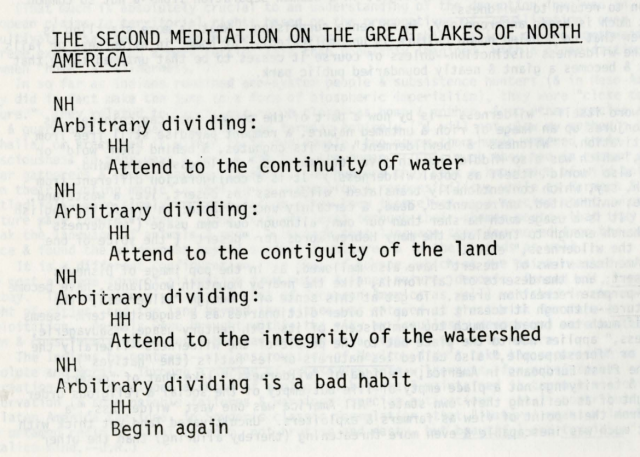

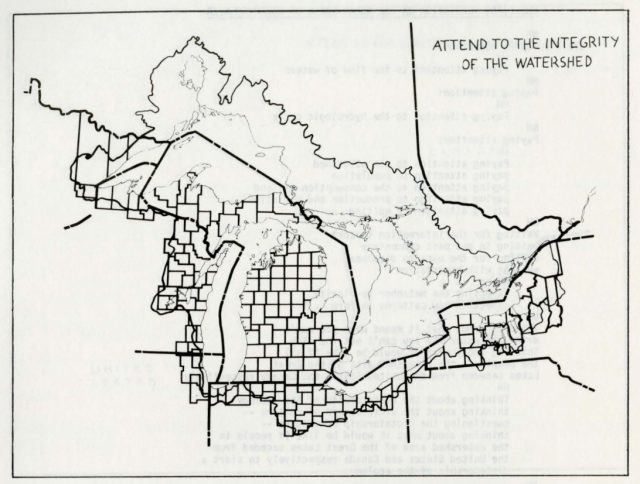

The Harrisons reply: "The bad habit of obeying the lines on the map that divide the Great Lakes in half, we said--part to Canada, part to the United States. And still worse, we said, dividing the land into successively smaller bits--states, counties, municipalities."

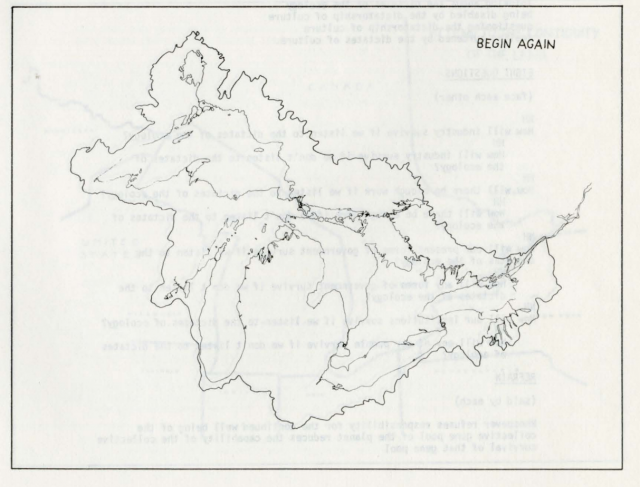

Here's the "Second Meditation on the Great Lakes of North America":

Begin again. Not this:

or this:

but this:

That was 1979. In the decades since, the Harrisons have done dozens of projects, many of which also strive to undo the "arbitrary divides" that prevent us from visualizing the contiguous megastructures of the natural world. Covering their body of work in depth is beyond the scope of this newsletter (you could always check out this retrospective, from 2016), but one project that stands out is their attempt, in 1993, to "image [the] North-South continuities" that comprise what remains of the North American Pacific Coast Temperate Rain Forest. This attempt to "network the watersheds" and discern "the eco-poetics of the whole" revealed a single "serpentine lattice" joined by "salient topographical features -- ridges, coastlines, and the lines formed by rivers, grouped in little leaf-like drain basins." (As a side-note, this 1993 usage of the term "eco-poetics" predates any other usage I could find by at least seven years, and they should probably be credited with coining the phrase.)

Cultural critic Michel de Certeau, writing on the Harrisons, remarks that "[e]verywhere the Harrisons introduce into their representations of things another way of seeing them: there are photographs, but they're painted, there are scientific maps, but they're revised (re-envisaged) by the future that is drawn on them." de Certeau argues that they aren't just using the "technical representation of an area" to show what the area really is, as I argue above, but also "as a tool [...] to see it as it will be, or as it could be."

I don't disagree. Indeed, a utopian streak--a view of the world as it could be--undeniably runs through these projects. Serpentine Lattice, the video installation that emerged as a result of their rainforest investigation, proposes that 1% of the Gross National Product be set aside to create a "gross national ecosystem." In a related article on "retrofitting biodiversity" they note that the expense of acquiring the land in the Lattice would be "[f]ar less than [the cost of developing] a four-lane interstate highway [...] Thereafter, regenerating topsoil where possible, an altered, more ecological type of forest farming could interchange with areas that would be left to succession, alternating the operations of cultural activity with ecological succession and establishing the operations of culture as figures within a biodiverse field."

From the video again: "Then / the gross national ecosystem / could take its place / privileged appropriately / as the field within which / the political systems / social systems / and business systems / that comprise / our eco-cultural identity / can exist."

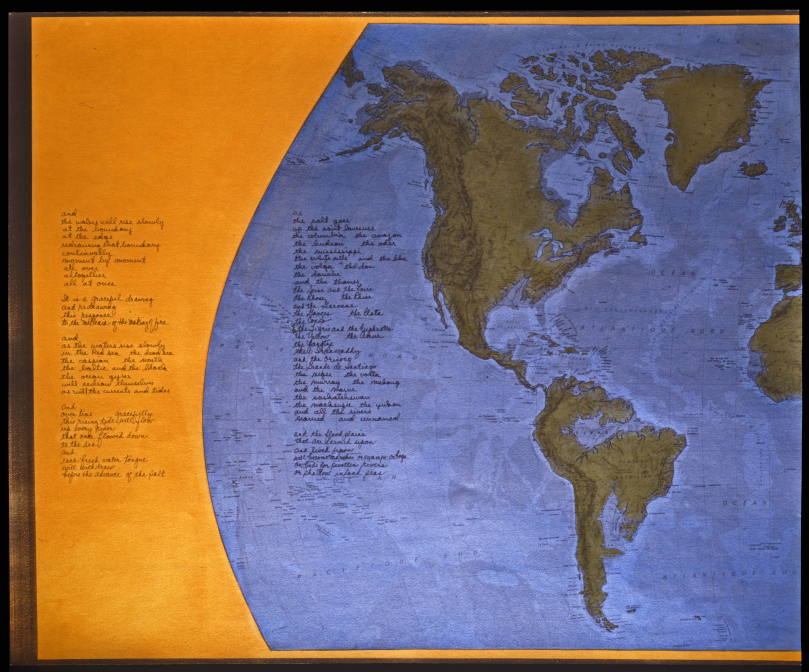

But let's place utopia aside for a moment. de Certeau writes that the Harrisons want to visualize the world not only as it could be, but also as it will be. Thinking about "the world as it will be" from an environmental perspective inevitably means grappling with climate change, and the potential devastation it will wreak on specific ecologies, especially riparian or floodplain ecologies. The Harrisons begin visualizing this as early as 1978's "The World Ocean is a Great Draftsman," in which "[a] high water line is drawn around the globe." This vision is refined in 1984 for The Book of the Lagoons, a seven-volume hand-made book accompanying their complex Lagoon Cycle. The seventh volume depicts the globe "as it will be" should the polar ice caps melt:

"[T]he flood plains," reads the text, "that are farmed upon / and lived upon / will become marshes or swamps or bogs / or beds for swollen rivers / or shallow inland seas."

In 2009, they founded the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure at UC Santa Cruz, devoted to bringing together "artists and scientists to design ecosystem-adaptation projects in critical regions around the world to respond to climate change."

As for the Harrisons themselves, their website currently reads "they are working simultaneously on Global Warming works at rather large scale. All assume ocean rise. They are looking at what that might mean for the upward movement of people beyond business as usual."

Helen Meyer Harrison died in 2018 at the age of 90.

--JPB // Dedham, MA, May 11, 2020 (revised Wednesday, May 13)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)