Wednesday Investigation 01: Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, and non-narrative film

"The cinema must therefore never copy the stage. The cinema, being essentially visual, must above all fulfill the evolution of painting, detach itself from reality, from photography[.]"

Dating from 1997, this is, I believe, the oldest notecard I have tagged investigate. If you can't read my handwriting, it directs me to look into two men, [Viking] Eggeling and [Hans] Richter, identifying them as having made "the first attempts at abstract film." This isn't entirely true, as it turns out! But more on that in a bit.

First, though, let's check these guys out. It's sort of weird to remember that in 1997 neither Wikipedia nor YouTube existed, but they do now, so I put them to use. From Wikipedia, I learned that Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling were European avant-gardists, both involved in the Dada movement. They're introduced to one another by Tristan Tzara in 1918, and they work together in Klein-Kölzig for a time, producing, among other things, a pamphlet about elementary pictorial elements, Universelle Sprache, or Universal Language. (There was a lot of this going around at the time, actually--if you're interested in the history of (mostly failed) attempts to come up with a cohesive "grammar" of pictorial elements, check out Johanna Drucker's fascinating book on the topic, Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production.)

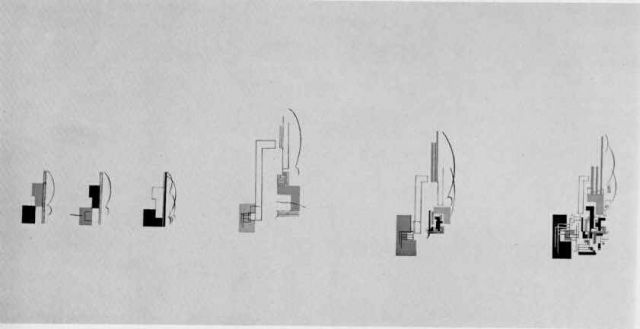

Eggeling, during this time, is experimenting with "picture rolls"--sequences of transforming geometric images painted on long scrolls, some up to fifteen meters in length. Richter also begins working on his own picture-roll sequence, Präludium.

Here's a slice of Präludium, and you can maybe see how it resembles sequential frames in an abstract film:

Eggeling makes this leap, and by around 1920 he's begun work on a film, Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe. Richter follows suit soon after. Their joint cinematic experiments get written up by Theo van Doesberg in a May 1921 issue of De Stijl, and if any of you speak Dutch you can read the article ("Abstracte Filmbeelding") here. Sadly, though, their collaboration is not to last: Eggeling leaves Klein-Kölzig in late 1921, and continues work on Horizontal-Vertikal-Messe in Berlin, though the film is never completed to Eggeling's satisfaction, and it seems that the incomplete versions are now lost.

So Richter beats Eggeling to the punch that year, successfully completing his own abstract film, Rhythmus 21, though it apparently isn't formally screened until 1923. YouTube has it. Eggeling labors for a few more years, struggling with technical difficulties, until he meets Bauhuas student Erna Niemeyer, who undertakes the animation work for Eggeling's new film project, Symphonie diagonale. Together, they overcome the technical hurdles and complete it in 1924. YouTube has this as well.

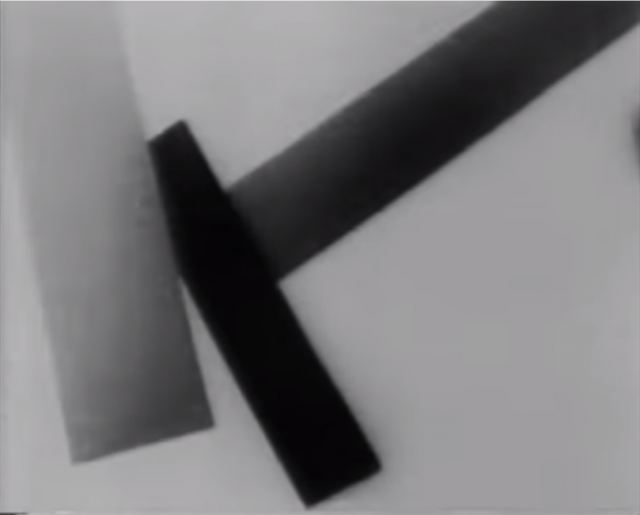

Both are worth a watch, but of the two, I prefer Symphonie diagonale. The rectangular forms that dominate Rhythmus 21 have a blunt, Suprematist appeal:

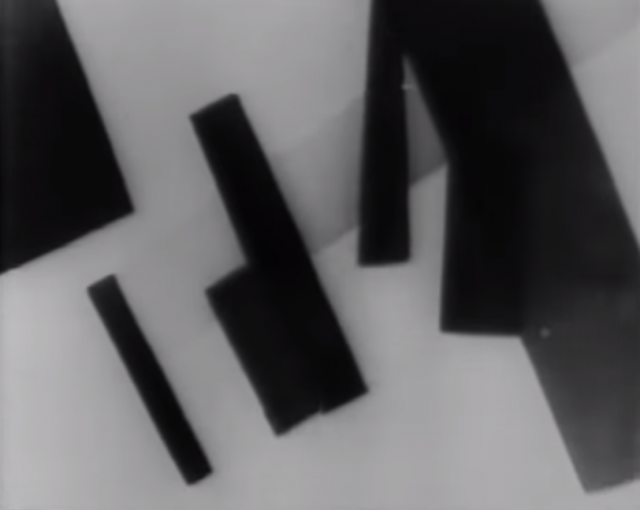

...but the forms in Symphonie diagonale are more intricate, and their interplay more complex.

These delicate forms flicker in and out, appearing and disappearing with stable periodicity (although Richter's film is called Rhythmus, Eggeling's is the one that feels more profoundly rhythmic to me). The finished product, at times, evokes the same pleasant feeling as standing a neon-lit street, watching geometries lighting themselves up and winking back out. Like a 1920s version of Gibsonian cyberspace.

It's a testament to the sexist hierarchies within our culture that Eggeling gets the credit here while Niemeyer, who solved many of the technical problems with regard to the animation, is basically relegated to footnote status. She doesn't even have her own Wikipedia page unless you go over to German Wikipedia, but she's worth investigating in her own right. She made a wide variety of artistic work, much of it under the name Ré Soupault. She's best known as a photographer, though she also made radio features, abstract carpets featuring Sanskrit, and "an experimental fashion film about shoes."

OK, so back to the question we raised at the outset: do Richter and Eggeling make "the first attempts at abstract film?" Not really. That credit usually goes to Italian Futurists Arnaldo Ginna and his brother Bruno Corra, who were allegedly handpainting films as early as 1910. In 1916 they co-author the manifesto "The Futurist Cinema," which contains a more-or-less recognizable description of abstract film: "The cinema must therefore never copy the stage. The cinema, being essentially visual, must above all fulfill the evolution of painting, detach itself from reality, from photography[.]" That same year they produce Vitta Futurista, often considered the first abstract film, but which is now lost.

Another candidate for "early attempter" might be Léopold Survage, who, in 1913, creates 100 watercolors / inkwashes that he intends to turn into a film called Rythmes colorés: he can't raise the money, so it doesn't happen, but it's undeniably an attempt.

We also have Walter Ruttmann, best known for his "city symphony" Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis. It's hard to know whether he "attempted" abstract film prior to Richter and Eggeling, but his Lichtspiel: Opus I is first screened in March 1921, which I think affords it the title of the oldest abstract film that you can still watch.

It's even, incredibly, in color:

This film is a remarkable technical accomplishment for its era, and the successful integration of animated images with a musical score (which dates back to the same period) makes it easy to draw a lineage between it and something like Disney's Fantasia. Ruttman's charming, borderline anthropomorphic blobs could slot right into the "abstract" segment of Fantasia and I don't think anybody would really bat an eye.

Honorable mention in this investigation must go to Philadelphian Mary Hallock-Greenewalt, who spends nearly two decades (1916-1934) working on a color-organ, the Sabaret, which relies on handpainted film with repeating geometrical patterns as part of its operation, though the Sabaret doesn't project images (it works more like a kinetoscope). Nevertheless, Hallock-Greenewalt is a fascinating figure (she earns nine different patents as she develops the Sabaret, including one for a type of rheostat--later in life she successfully sues General Electric for patent infringement). The Sabaret is part of a larger visual music theory she espouses called Nourathar, and she is the author of a 1946 book: Nourathar: The Fine Art of Light-Color Playing. This article on Hallock-Greenwalt is fascinating, and performance artist/hacker/algorithmic filmmaker Amy Alexander runs something called the Mary Hallock Greenewalt Visibility Project, which some of you may enjoy checking out.

JPB // Dedham, MA, April 22, 2020 (revised Wednesday, April 24)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:15]: Blind spots, part two](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/jeph-jerman.jpg)

![Wednesday Investigations [2:14]: Blind spots](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/takehisa-kosugi.jpg)