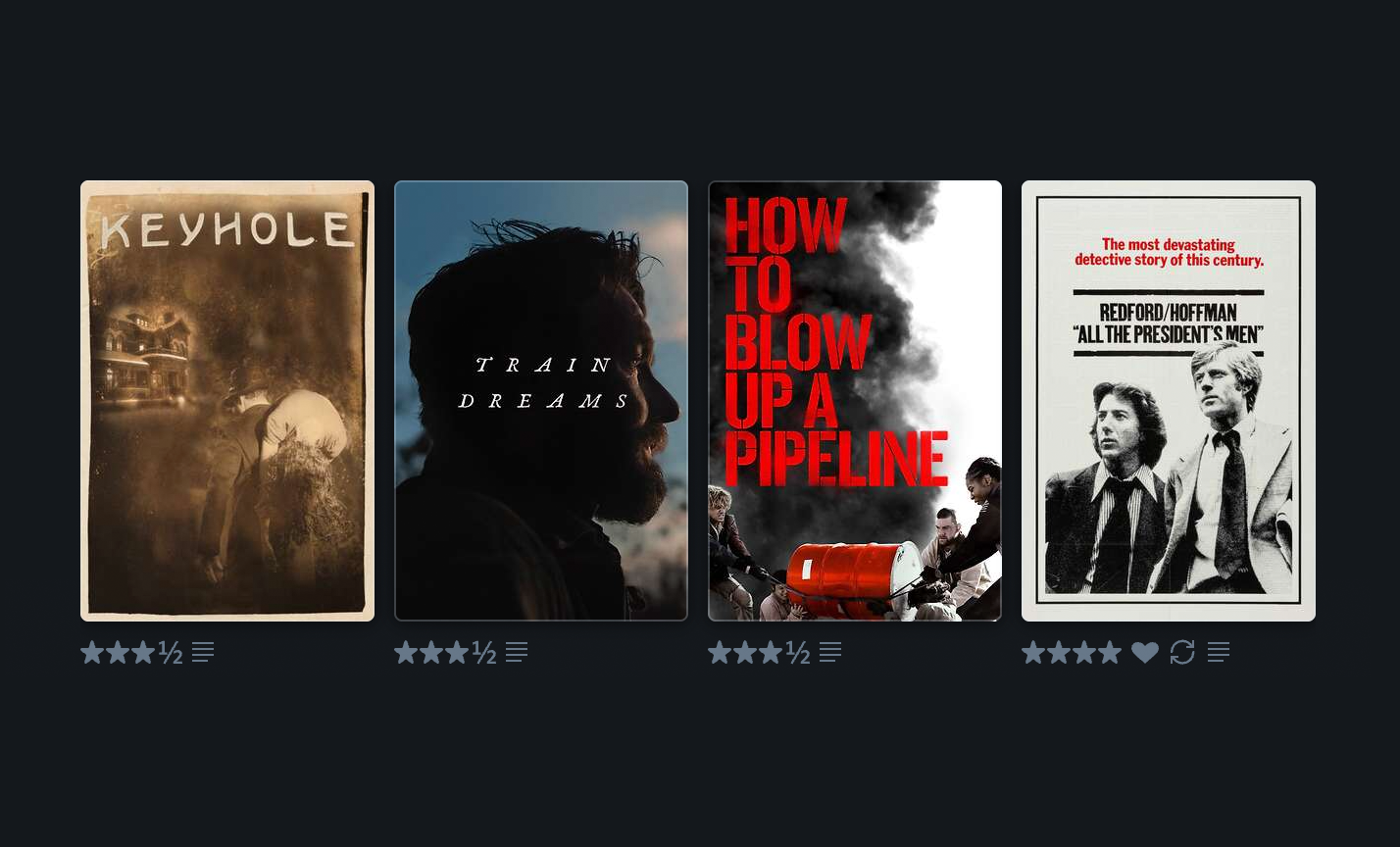

11/27-12/1

Guy Maddin's KEYHOLE // Clint Bentley's TRAIN DREAMS // Daniel Goldhaber's HOW TO BLOW UP A PIPELINE // Alan J. Pakula's ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN //

Guy Maddin's KEYHOLE

Maddin's films tend to be resistant to straightforward summary, and just trying to articulate what literally happens on screen here may prove the point. Nevertheless, here's what we got: a multigenerational psychosexual scenario unfolds in the upper floors of a haunted house, while on the lower floors a bunch of gangland characters (including one played by Kevin McDonald from the Kids in the Hall) embark upon a redecorating project, which includes cobbling together a functional electric chair. Perhaps Maddin's own brief summary—it's about a house where "all sorts of sad and horny things happen"—is better. Isabella Rosselini is here, and Udo Kier (RIP) passes through. More uneven then Maddin's best work, and it loses points for being the second film I've seen this week where a spectral Chinaman glowers meaningfully but doesn't deliver dialogue (Train Dreams was the other one). But a second-tier Maddin film still has more life in it than a second-tier film from just about anybody else working today.

Clint Bentley's TRAIN DREAMS

I have often said that the literary form best suited for filmic adaptation is not the sprawling, multivalent, capital-N Novel but rather the more modestly sized but still substantial lower-case-n novella, and I'm more than ready to seize upon this film (based on Denis Johnson's novella) and The Life of Chuck (based on Steven King's novella) as validatory evidence for this point: both are modestly sized but still substantial lower-case type films, broadly pleasant, competently made, economically thrifty--in a word, successful. We would do well to have more films like this, and, for that matter, we would do well to have more novellas, and Hollywood's interest in the form can only be a good thing.... And yet a nagging voice remains. Films with small-scale ambitions can risk becoming slight; the warm satisfactions of their tidy epiphanies can risk becoming gauzy. Life of Chuck runs these risks and so does this: I enjoyed just about every moment as it flickered before me but I'm not sure if I'll remember a single frame by this time next year (though odds are even that I'll hold on to William H. Macy's fine turn as the dotty old-timer with the demolition equipment.)

Daniel Goldhaber's HOW TO BLOW UP A PIPELINE

<spoilers> It's not hard to imagine a better version of this film—one where the performances are a bit more nuanced, the tension a bit more palpable, the editing a bit more taut. But I think this succeeds on its own merits--as a proudly low-budget realist, character-driven thriller--and I must say that I was happy that the film doesn't hedge from its premise: although it acknowledges that the titular act may have some morally questionable overtones, it largely commits to making an argument for its ethical justness, and it doesn't cop out at the last second and turn it into a "crime doesn't pay" story or engage in "yes, but at what cost" handwringing. I'm not saying a film has to share my politics to be good, but I am saying it's refreshing to see a film that commits to a set of genuinely counterhegemonic convictions, that wants to do more than just flirt noncommittally with leftist politics (or, worse, to borrow cynically from leftist aesthetics as a source of attractive people and a vibes-based authenticity that can be discarded once it's narratively inconvenient).

Alan J. Pakula's ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN

This fall, I watched all three films in Alan J. Pakula's "paranoia trilogy"—KLUTE, THE PARALLAX VIEW, and this—while they were available through Criterion. Of those three, I feel like this is the one people hold in the highest critical regard, so is it blasphemous to say that I preferred THE PARALLAX VIEW? All three films have similar strengths—obviously the pervasive paranoid vibes, but also breathtaking cinematography and strong performances by world-class leading men (Redford and Hoffman here, obviously; Warren Beatty in THE PARALLAX VIEW; Donald Sutherland in KLUTE). And yet THE PARALLAX VIEW has the most range to its setpieces: it has a car chase, a bar fight, an assassination, a suspenseful sequence with a bomb on a plane, and a weird experimental film-within-a-film right at its center. ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN, by contrast, has the least range—in fact, it basically has only one mode: since the work of the investigation is two guys mostly attempting to reverse-engineer an org chart with help from the world's most reluctant people, the film can only really give us scenes wherein they are cleverly teasing incremental bits of detail out of squirrelly men and women. As it happens, this is pretty fun to watch, so even though Redford and Hoffman are basically doing the same thing over and over, Pakula juices up these endeavors with a remarkable amount of variety, assisted no doubt by the winning charisma that these two actors bring to the table. Nevertheless, by the time the credits roll, this mode feels pretty exhausted, enough so that you can accept the film's abrupt ending. (Pakula elects to jump from mid-investigation straight to Nixon's resigning, and for a moment you feel cheated—why didn't we follow the conspiracy all the way through to its final unraveling?—but you also find yourself feeling that you might rather not watch another hour of tense conversations just to get there, and maybe the choice to just skip to the end is for the best.) Still a marvelous watch by any measure.